Introduction

In this blog post we learn how to perform a fuzzing test against a 802.11 authenticator (better known as Access Point). We will use boofuzz, the successor of the well-known Sulley fuzzing framework.

WPA3 is slowly emerging in the 802.11 modem and router industry. There aren't many devices yet, but production of WPA3 certified devices is expected to increase in the foreseeable future. This means that there will be a additional PAKE key exchange that is plugged in front of the old 4-way handshake, which is part of WPA and WPA2. This new handshake ensures two additional security properties:

- Perfect forward secrecy: Once a key was revealed, it cannot be used to decrypt past sessions

- Offline dictionary attack resistance: When recording the handshake exchange by a passive observer, the material collect cannot be used to launch a passive dictionary attack against the handshake. For example with the WPA 4-way handshake, a passive listener in the BSS can obtain key exchange data and launch a offline brute force attack on amazon web services with high computing resources.

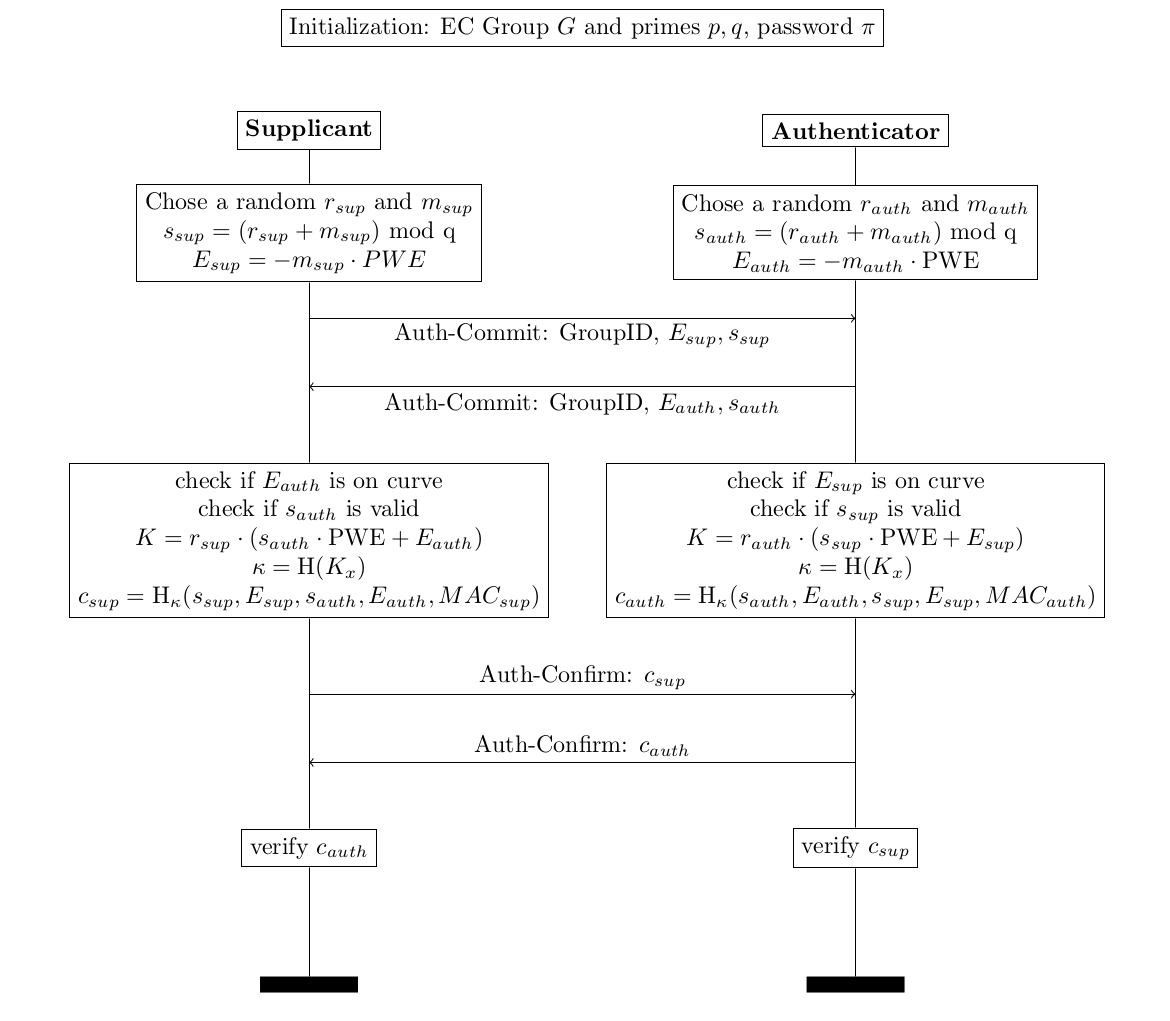

This Dragonfly handshake basically consists of two steps:

- Auth-Commit exchange: A online guess at the password is launched

- Auth-Confirm exchange: Common knowledge of the password is confirmed

Dragonfly is a password authenticated key exchange (PAKE). PAKE schemes essentially solve the asymmetric key distribution problem. The issue with public key cryptography is the difficulty of trust. For this reason a whole public key infrastructure based on certificates exists that essentially makes statements who is who and whom can be trusted.

Dragonfly is similar to the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. However, a important difference is that Dragonfly is authenticated. Diffie-Hellman is not authenticated, which is also the reason that attackers can launch a man in the middle attack against it. The Dragonfly participants need to possess a low entropy common secret (your wifi password) in order to exchange a secrete key. The password hashed together with the MAC addresses is used to derive a group element in the elliptic curve group. Then this group is used as a starting point of a modfied Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Without the correct password, an attacker cannot find the equivalent group element. Sounds complicated? Well it is.

Why fuzzing?

Fuzzing is a common technique to trigger memory corruption vulnerabilities by creating and sending malformed inputs to the software being tested.

In years 2007 to 2009, Laurent Butti found many security vulnerabilities by using the predecessor of boofuzz, Sulley. He fuzzed mainly authentication and association 802.11 management frames.

Not much has been done with fuzzing in the 802.11 security research since then. For this reason, I launched another attempt at the newly developed software for the WPA3 Dragonfly handshake.

Recently, the infamous researcher Maty Vanhoef (crack attacks) has published a couple of new security vulnerabilities in his recent paper Dragonblood. He mainly focuses on timing and and cache based side-channel attacks.

But why should we attempt to fuzz Dragonfly? After all, there are only two management frames exchanged in the authentication. There are a couple of reasons:

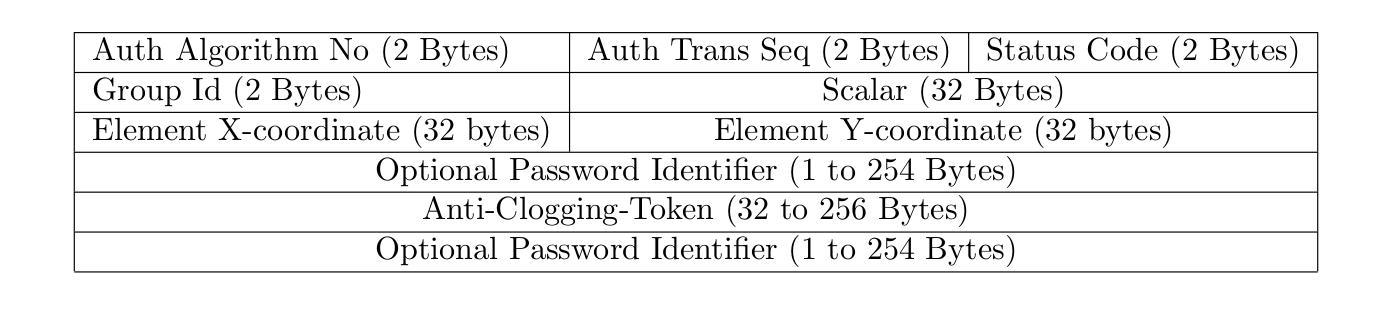

Anti Clogging Tokens

Deriving the password element in the beginning of the Dragonfly handshake is a computationally costly operation. Therefore, the handshake is secured against DoS by a secret cookie that needs to be reflected when the AP sends it to the station. This cookie is essentially a SHA256 hash over the MAC addresses of the supplicant and a server secret. The anti-clogging token has no pre-defined length in the RFC. This means vendors have free choice there.

So if a supplicant sends an SAE auth-commit frame to the access point and the access point responds with a auth-commit frame with status MMPDU_STATUS_CODE_ANTI_CLOGGING_TOKEN_REQ set, the client has to reflect the cookie in a new auth commit frame. This exchange may produce interesting fuzzing possibilities:

- What happens when the client sends a auth-commit frame with the reflected anti-clogging token but a different payload? Different group id? Or same group id but cryptographic payload for FFC instead of ECC?

Password Identifiers

Dragonfly authentication frames may include a password identifier. Password identifiers are labels that are mapped to a certain password. They are used to tell the AP what password should be used for the authentication. The function below shows how password identifiers are parsed in hostapd 2.8. So each password identifier has a 3 byte header. A password identifier is located after the scalar and elements or after the scalar and elements and a potential anti-clogging token. There is no real standardization where the password identifier must be located.

static int sae_is_password_id_elem(const u8 *pos, const u8 *end)

{

return end - pos >= 3 &&

pos[0] == WLAN_EID_EXTENSION &&

pos[1] >= 1 &&

end - pos - 2 >= pos[1] &&

pos[2] == WLAN_EID_EXT_PASSWORD_IDENTIFIER;

}

Even the source code responsible for parsing the password identifier complains about the ambiguity of parsing the password identifier.

static void sae_parse_commit_token(struct sae_data *sae, const u8 **pos,

const u8 *end, const u8 **token,

size_t *token_len)

{

size_t scalar_elem_len, tlen;

const u8 *elem;

if (token)

*token = NULL;

if (token_len)

*token_len = 0;

scalar_elem_len = (sae->tmp->ec ? 3 : 2) * sae->tmp->prime_len;

if (scalar_elem_len >= (size_t) (end - *pos))

return; /* No extra data beyond peer scalar and element */

/* It is a bit difficult to parse this now that there is an

* optional variable length Anti-Clogging Token field and

* optional variable length Password Identifier element in the

* frame. We are sending out fixed length Anti-Clogging Token

* fields, so use that length as a requirement for the received

* token and check for the presence of possible Password

* Identifier element based on the element header information.

*/

tlen = end - (*pos + scalar_elem_len);

if (tlen < SHA256_MAC_LEN) {

wpa_printf(MSG_INFO,

"SAE: Too short optional data (%u octets) to include our Anti-Clogging Token",

(unsigned int) tlen);

return;

} else {

wpa_printf(MSG_INFO,

"SAE: Potential Anti-Clogging Token");

}

elem = *pos + scalar_elem_len;

if (sae_is_password_id_elem(elem, end)) {

/* Password Identifier element takes out all available

* extra octets, so there can be no Anti-Clogging token in

* this frame. */

return;

} else {

wpa_printf(MSG_INFO,

"SAE: No password ident after scalar and element");

}

elem += SHA256_MAC_LEN;

if (sae_is_password_id_elem(elem, end)) {

/* Password Identifier element is included in the end, so

* remove its length from the Anti-Clogging token field. */

tlen -= 2 + elem[1];

} else {

wpa_printf(MSG_INFO,

"SAE: No password ident after scalar and element and anti-clogging-token");

}

wpa_hexdump(MSG_INFO, "SAE: Anti-Clogging Token", *pos, tlen);

if (token)

*token = *pos;

if (token_len)

*token_len = tlen;

*pos += tlen;

}

Vendor Specific Parsing

The discussion in IEEE groups show impressively that the programmers have many misunderstandings and misconceptions about the implementation of Dragonfly. This is usually a good indicator that there will be errors.

Multiple Cryptographic Structures supported

Dragonfly supports Finite Field Cryptography and Elliptic Curve Cryptography. This means that the kind of cryptography has to be detected on contents of the frames. This is bad practice at least. Most real world implementations exclusively use ECC.

Setting up the testing environment

Playing around in 802.11 involves a lot of pain and frustration. Often things don't work out as described in the Internet. In the following section, we will use the awesome mac80211_hwsim radio simulation kernel module. All software and instructoins have been tested an run on Ubuntu 18.04.

The testing environment is created via hardware simulation of WiFi radios.

# kill all interfering daemons such as network-manager

sudo pkill wpa_supplicant

sudo service network-manager stop

# create 3 virtual 802.11 radios named wlan0, wlan1, wlan2

sudo modprobe mac80211_hwsim radios=2

rfkill unblock wifi

Enable monitoring of radio simulation traffic in wireshark with:

sudo ifconfig hwsim0 up

Now you may observe the simulated traffic on the interface hwsim0.

Before Fuzzing

Sources: 1. How to use raw sockets in 802.11 2. Injection Test

Before starting, it might be worthwhile to find out the details of your wireless card. You can do so with the command sudo lshw -class network. In my case, the output is the following:

$ sudo lshw -class network

[sudo] password for nikolai:

*-network

description: Wireless interface

product: Centrino Advanced-N 6235

vendor: Intel Corporation

physical id: 0

bus info: pci@0000:02:00.0

logical name: wlan0

version: 24

serial: 00:00:00:00:00:00 # i changed this for obvious reasons

width: 64 bits

clock: 33MHz

capabilities: pm msi pciexpress bus_master cap_list ethernet physical wireless

configuration: broadcast=yes driver=iwlwifi driverversion=4.15.0-39-generic firmware=18.168.6.1 ip=192.168.0.4 latency=0 link=yes multicast=yes wireless=IEEE 802.11

resources: irq:32 memory:f7d00000-f7d01fff

This gives you the interface name, driver used, MAC address of the card and so on.

In order to send management, data or any type of pure raw packet from a wireless interface you have to do the following:

Make sure the wireless interface hardware supports packet injection in monitor mode.

- To check the capabilities of your WiFi card, you can check the following command:

iw list | grep -A7 "interface modes:"If it outputs monitor, you are good to go. - To confirm injection tests, you can use

aireplay-ng -9 -e teddy -a 00:de:ad:ca:fe:00 -i {AP interface} {STA interface}

Then put the wireless interface in monitor mode with

# the first commands kill interfering processes

airmon-ng check kill

service network-manager stop

pkill wpa_supplicant

# this puts the card in monitor mode

ifconfig {dev} down

iwconfig {dev} mode monitor

ifconfig {dev} up

# this sets the appropriate channel

iwconfig {dev} channel {channel}

Then you can create a raw socket in python via

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

s.bind((dev, ETH_P_ALL))

Finally, Build and append at the beginning, the appropriate radiotap header while building your wireless 802.11 packet for management and control frames. Since you are basically bypassing all lower lever wireless drivers (which handles management and control frames), it becomes your job to include the radiotap header. Info about radiotap header.

Radiotap Header

We need to include a radiotap header in our raw frames.

The radiotap header format is a mechanism to supply additional information about frames, from the driver to userspace applications such as libpcap, and from a userspace application to the driver for transmission. Designed initially for NetBSD systems by David Young, the radiotap header format provides more flexibility than the Prism or AVS header formats and allows the driver developer to specify an arbitrary number of fields based on a bitmask presence field in the radiotap header (Source)

The radiotap header is not actually included in 802.11 frames that are sent over the air, it is merely an additional layer of information that is added by the wireless device/driver and passed into userland. A very good introduction by Andy Green to radiotap headers can be found here. The 802.11 driver subsystem mac80211 requires all injected packets to have a radiotap header. Another very good blog post that explains the linux wireless subsystem and the paths that management frames and data frames take within the 802.11 linux system.

Now the question poses itself if it is possible to fuzz radiotap headers?

We will use the smallest possible radiotap header in dragonfuzz.py and let the 802.11 driver derive the proper values.

# no flags present, let the 802.11 driver add the stuff

DEFAULT_RADIOTAP_HEADER = b'\x00\x00\x08\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'