Here is a quick link to download my Master Thesis about fuzzing the WPA3 handshake.

In the past couple of months, I completed my Master thesis at Humboldt University and thus finalized my computer science degree.

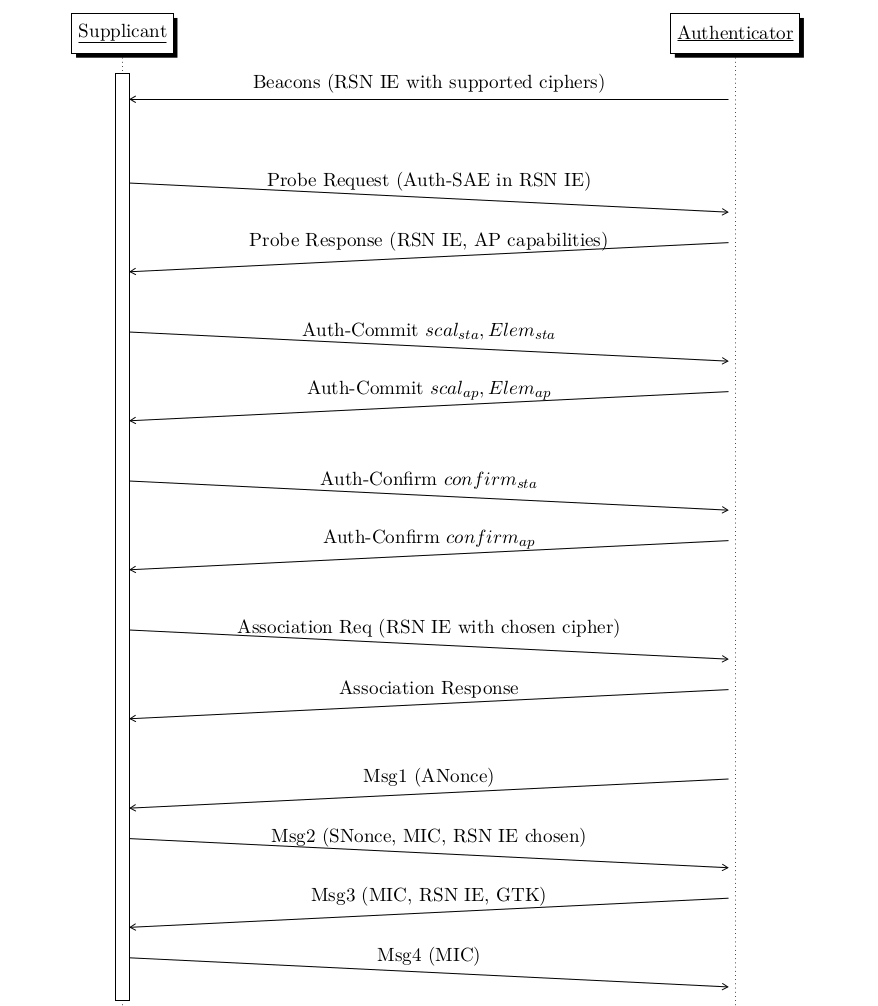

The aim of this scientific thesis was to find a suitable approach to systematically fuzz the new WPA3 Dragonfly handshake that is plugged in front of the quite old WPA 4-Way handshake. The research yielded different fuzzing policies and I learned a lot about systematically fuzzing complex software projects.

Why do we even require a third WPA version?

The purpose of the now 15 year old 4-way handshake of WPA and WPA2 is to establish a so called Pairwise Transient Key (PTK) that is used to decrypt all traffic between the client (supplicant) and authenticator (access point). With WPA-PSK (pre-shared key), commonly a password that both the supplicant (for example your mobile phone) and the authenticator (the router that sits in your apartment) possess, is used to derive the PTK in a sequence of 4 EAPOL key frames.

This old 4 way handshake is still reasonably secure when used with high entropy passwords. However, we human beings tend to use easy guessable low entropy passwords such as baconbacon, which is the WiFi password that my hostel uses in Krabi/Thailand from where I am writing this blog post.

The classic 4-way handshake is susceptible to offline dictionary attacks. Furthermore, since deauthentication frames are not encrypted and can easily be spoofed (which means that you can pretend to be a network participant who you are not), it is possible to deauthenticate a client from the access point, observe the network and wait until the client reconnects with the access point and capture and record the key material that is exchanged.

With this collected key exchange material it is feasible to launch a offline dictionary attack against the password. In practice, this means you upload a highly optimized cracking program to the AWS cloud and pay a couple of hundred dollars to enumerate all wordlist passwords, some rainbow tables and probably all combinations of lowercase alphanumeric strings up to 8 characters.

With WPA3, this offline dictionary attack and deauthentiation attack are no longer feasible.

Security Properties of Dragonfly

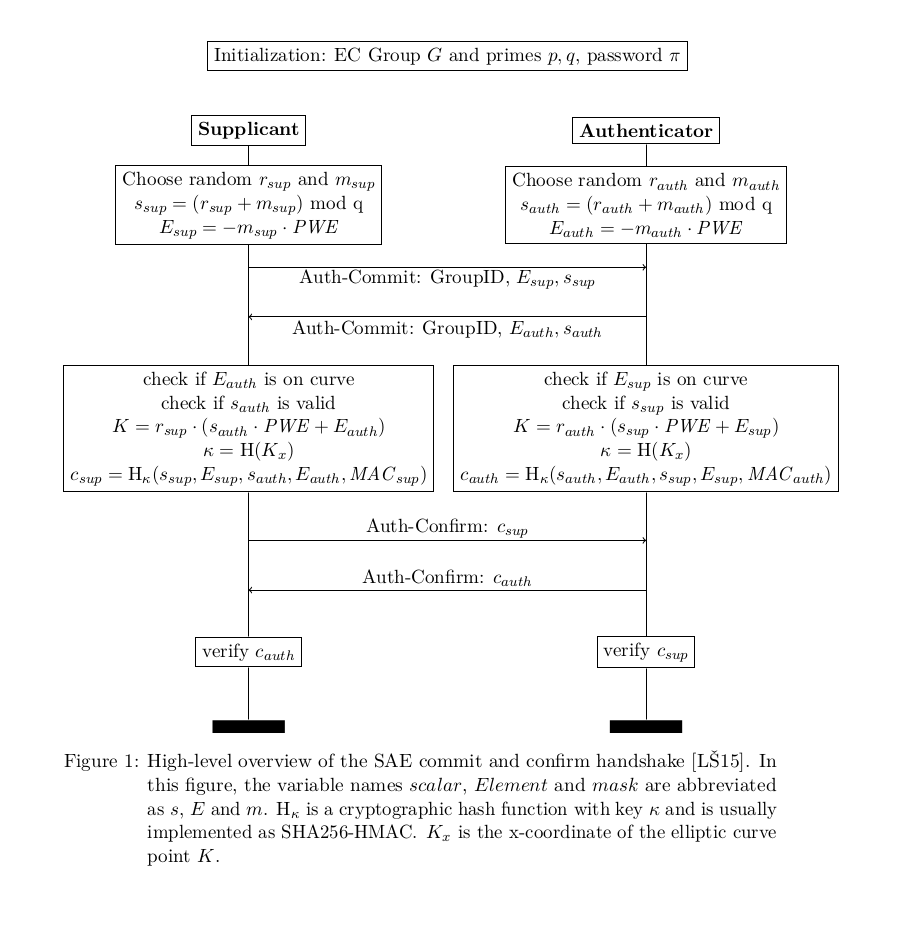

This new Simultaneous Authentication of Equals handshake (another name for the Dragonfly handshake), which was originally standardized in 2011, adds two security properties to Wi-Fi’s original 4-way handshake:

- Forward secrecy. Attackers cannot decrypt traffic with old keys, because the negotiated keys are updated in every new instance of the handshake.

- Offline dictionary attack resistance. Attackers can merely launch online attacks against the handshake. Put differently, the number of guesses from a brute force attack grows linearly with the number of authentication attempts, which can easily be regulated by the authenticator.

Put differently, the Dragonfly handshake is a so called PAKE scheme that enforces the two participants to make an online guess at the password. Online in this context means that it's impossible to capture viable key material in order to crack it offline. PAKE stands for Password Authentiated Key Exchange and one important property of PAKE schemes is that they are capable of securely exchanging a key, while simultaneously being authenticated.

It's the same principle as with the well-known Diffie-Hellman key exchange, except that the exchange is authenticated, which means that only two parties that share a common key are able to exchange a key.

Therefore, the sole purpose of the Dragonfly key exchange is to take the PSK as input, somehow construct a common base element in a discrete logarithmic group (such as elliptic curves or multiplicative groups modulo a prime p). The plaintext password (PSK) and some large random numbers are used as ingredients to derive the common base element in order to establish an high entropy commonly shared key PMK that is used as an input to the old 4-way handshake.

Because the random numbers change in every iteration of the Dragonfly protocol, the PMK is unique for each new instance of the handshake. Now, it's easy to see why an offline dictionary attack is unfeasible and why forward secrecy is guaranteed.

Why did the inventor of Dragonfly - Dan Harkins - not simply use an existing PAKE protocol? The reason were licensing issues with the original SPEKE protocol.

What is fuzzing?

Fuzzing is a testing strategy whose intention is to uncover security vulnerabilities in the software under test. It is the process of repeatedly running a program with generated inputs that may be syntactically or semantically malformed.

A possible definition of fuzzing as Valentin at al. understands it is the execution of the program under test using inputs sampled from an input space that protrudes the expected input space of the program under test.

In my master thesis, I mostly used a blackbox fuzzing approach and greybox fuzzing approach.

Blackbox fuzzing

In blackbox fuzzing, the logic and internal behavior of the fuzzed program is largely unknown. A blackbox fuzzer merely observes the input/output behavior of the program under test, thus treating the targeted software as blackbox.

An example for black-box fuzzing test is the generation of a large corpus of fuzzed jpeg files and uploading them to an arbitrary web jpeg compression service and observing if the service crashes in an unexpected way, typically revealed by 500 internal server error responses. Most traditional fuzzers have been blackbox fuzzers.

Coverage-guided greybox-fuzzing

Coverage-guided greybox-fuzzing (CGF) uses lightweight binary program instrumentation to trace the code coverage reached by fuzzed input mutations.

Greybox fuzzers typically obtain limited information about the internals and semantics of the program under test, such as performing lightweight static analysis or collecting dynamic information about code coverage by instrumenting the code at compile time.

In order to instrument programs, greybox fuzzing engines inject few code instructions right after every conditional jump. Those code instructions are called trampolines and their purpose is to assign a unique identifier to the current branch and increment a coarse counter belonging to the branch. The counter is implemented as probabilistic data structure such as a count-min sketch or Bloom filter. This instrumentation enables the fuzzer to keep track of what branches are how often executed. The instrumentation is applied at compile-time to the program under evaluation.

When the greybox fuzzing engine learns that a specifically mutated seed input explored previously unknown code paths, it adds the modified seed to an growing seed corpus. In other words, greybox fuzzers leverage coverage feedback information to find new inputs that reach deeper into the program.

CGF does not require manual program analysis, thus being more scalable and parallelizable compared to other whitebox fuzzing strategies. Put differently, CGF fuzzing engines combine various powerful concepts to yield efficient fuzzing campaigns.

What results did the WPA3 Dragonfly fuzzing methodology yield?

Unfortunately, the thesis did not yield similarly spectacular results compared to my Bachelor Thesis. However, I managed to gather some interesting insights and suggestions for further fruitful work:

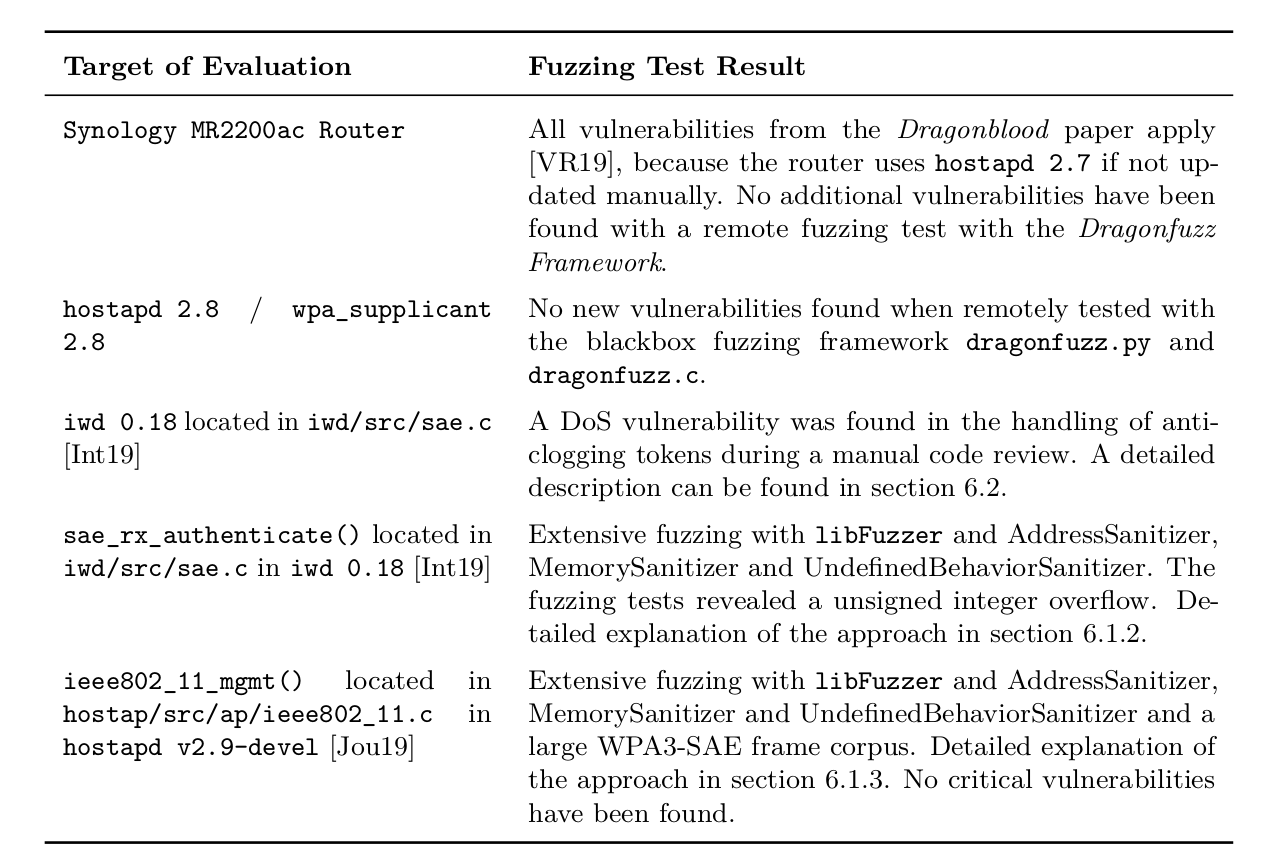

I managed to find a DoS vulnerability in the handling of anti-clogging tokens in the iwd intel wireless daemon. The vulnerability can be triggered remotely and it is possible to completely block any supplicant that tries to connect to the BSSID. The vulnerable function is called sae_process_anti_clogging located in the file iwd/src/sae.c in version iwd v0.18.

Ironically, the anti-clogging defense of WPA3-SAE tries to mitigate DoS attacks that arise when an attacker floods the victim with many forged commit frames which invoke a cascade of costly commit frame processing operations such as password element derivation, quadratic residue blinding and the mitigations against side channel attacks and timing attacks themselves.

static void sae_process_anti_clogging(struct sae_sm *sm, const uint8_t *ptr,

size_t len)

{

/*

* IEEE 802.11-2016 - Section 12.4.6 Anti-clogging tokens

*

* It is suggested that an Anti-Clogging Token not exceed 256 octets

*/

if (len > 256) {

l_error("anti-clogging token size %zu too large, 256 max", len);

return;

}

sm->token = l_memdup(ptr + 2, len - 2);

sm->token_len = len - 2;

sm->sync = 0;

}

The vulnerability is a signed unsigned integer overflow in the len variable which occurs when the anti clogging frame has a payload of 0 or 1 bytes. Technically, iwd allows to construct such as frame, even though it doesn't make any sense in a real world application, because the anti-clogging token payload should be a high entropy hashed secret that is verified by the issuer. More details can be found in the thesis in section 6.2.

-

Furthermore, I created a blackbox fuzzing client that remotely fuzzes any WPA3 capable authenticator. The link to the source code of dragonfuzz can be found here.

-

Another fuzzer is based on the boofuzz framework and can be found on github.

-

It wasn't straightforward to correctly compile and target the functionality that is responsible for the framing of the WPA3 handshake within

hostapd. Hence, I also published the instructions how to fuzz hostapd with libFuzzer on Github.

Creating an efficient fuzzing interface for a large software project such as hostapd was a lot of work, so I hope it helps someone.

While running the fuzzer for a couple of minutes, a unsigned integer overflow similar to the one that lead to the DoS above was reported by libFuzzer. However, it didn't have any harmful consequences.

Limitations of the fuzzing approach

The SAE handshake consists of only two frames with a total of five possible fields in the Auth-Commit management body (group id, scalar, element, optional anti-clogging token, optional password identifier) and only two possible fields in the Auth-Confirm frame (send confirm number, confirm token). Therefore, the parsing of those two authentication frames has limited complexity and thus the likelihood of programming mistakes in the parsing code is similarly slim. Hence, a solely fuzzing based approach as conducted in this thesis covers a fraction of all existing vulnerability classes.

Conclusion

Writing an efficient fuzzer that targets the WPA3-SAE authentication handshake in the wild is a difficult assignment, because there exists almost no hardware that supports the WPA3-SAE handshake at the time of writing this thesis (August 2019).

Instead a hybrid approach was followed. One method was the in-process, coverage-guided greybox fuzzing of the open source WiFi supplicant iwd and access point implementation hostapd with the fuzzing engine libFuzzer.

Another fuzzing strategy was a remote, over-the-radio blackbox fuzzing of the Synology MR2200ac Router, one of the rare devices that already supports the new WPA3 certification. Remote fuzzing was conducted with a fuzzing framework named Dragonfuzz that was developed during this thesis.

As a concluding statement, the author conjectures that a fuzzing based approach using modern, powerful greybox fuzzing engines such as AFL or libFuzzer is only meaningful, if the target of evaluation is rich in parsing functionality. This is not necessarily the case with WPA-SAE implementations, where parsing is limited to a few fields of static size. The room for logical flaws such as timing attacks or cryptographic implementation mistakes is much larger, as recent research has proven.

A manual security audit that checks for logical vulnerabilities is probably more successful in uncovering security vulnerabilities compared to a automated fuzzing based methodology. However, such a manual review process requires extensive experience from the auditor in various areas of computer security research in order to yield potential results.

Nevertheless, the research conducted in this thesis yielded a harmful DoS vulnerability in the 802.11 supplicant software iwd and thus justifies the chosen methodology.